India has two streams of classical music: that of the north, known as “Hindustani” and that of the south, known as “Carnatic”. Hindustani music has three major classical vocal traditions: Dhrupad (originally Dhruvapad – i.e. containing centrally repeating pattern), khayal (literally means “Concept”) and thumari.

Dhrupad is a style dedicated to an austere rendition. This tradition is the oldest of the three, generally dating pre-mugal period, and is a bit rigid. This style is essentially going extinct today. Except for a few exponents such as Daagar Brothers, what we hear today is the khayal style. The khayal has a greater degree of freedom compared to dhrupad. The khayal became popular during and after the times of emperor Akbar of India. Akbar’s great court musician Tansen popularised this style that is still adhered to practiced, performed and taught to students both on instruments and in voice. Generally what you hear today as “Indian Classical Music” is in khayal style. Thumari is the lighter style, and has a greater degree of freedom of expression through choice of notes. Although, a lighter and least rigid among the three classical styles, it is probably the most difficult one requiring greater talents. The apparent “freedom” of selection of notes, not afforded in khayal and dhrupad style, requires great skills. The selection of notes must be judicious in the amount of usage and at correct places, so as to intensify the emotions and beauty. Unlike in khayal style, where variations are sparingly embedded around the central theme, in thumari, the variations from central musical structure are quite pronounced and key to the development of the composition.

Besides these, there are many lighter semi-classical and folk forms such as bhajans, dadra, tappas, ghazals and quawwali. Bhajans are generally spiritual songs of Hindu traditions. Dadras are in 6-beat tala (called dadra too) and often part of the folk traditions. Tappas are usually composed in kafi-class of ragas. Gazals and quawwalis are generally compositions of Islamic origin.

Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Dha Ni are the seven swars or the seven notes that make up the scale. The scale is similar to a western scale; however there are many microtonal structures (called shrutis) in-between each swar. In Indian classical music, the artist tries to invoke one of nine major emotions (called rasas), which are associated with the musical composition, called a raga. A raga is a musical composition based on specially designed ascending (called aroha) and descending (called avaroha) scales for that raga. For example, raga “desh” only allows five notes in ascend (Sa, Re, Ma, Pa, Ni; all natural notes), but allows all seven notes in descend (Sa, Ni-flat, Dha, Pa, Ma, Ga, Re, Ga, Sa), such that the seventh note Ni must be flat and only allowed in descend. By proper rendering of the notes, in their traditional patterns and styles, a performer can create a unique artistic exposition of that raga in every performance. Performing a note out side the scale of the raga is strictly forbidden in dhrupad or Khayal styles. In thumari style, variations outside the raga scale are allowed, but require great skill and training to accomplish it successfully. That is why thumaris are not ragas but are based on one or more ragas. The lyrics of a raga or a thumari (in the classical music) are usually spiritual in nature, because music in general was for spiritual purposes. There are thousands of ragas, but only a couple hundred at the most are regularly performed.

Many of the Prabhat Samgiit songs are based on the classical backgrounds of these ragas such as Bhairavi, Darbari Kanada, Malkauns, Chandrakauns, Kafi, Todi, Miya ki Malhar, Desh, Kedar, Bhimpalasi, Chhayanat, Pahadi, Shiva Ranjani, Yaman Kalyan, Bageshri, Jayjayvanti, Asavari, Jaunpuri, Khamaj, Deshi, Piloo, etc.

Some of the Prabhat Samgiit songs are in folk styles of dadra, gazals and quawwalis. A few songs are also based on themes from western tunes from Scandinavia etc.

Prabhat Samgiit collection also includes Padya (poetry) Kirtans. Traditionally these Kirtans are sung in Dhrupad style. The lyrics are about spirituality and often about the life of Krishna. Couplets of the lyrics are sung in slow dhrupad-type measures by the lead singer, and their significance is elaborated in recitation. The group of singers responds to the lead singer in quicker and quicker tempo, until the chorus finishes in a crescendo. Then the leader recites the next couplet again. The process goes on until a particular episode is completed. Tanpura and khol (special type of drum) are used for the accompaniment. In recent times the harmonium, violin, esraj, and sarangi are also used. The Kirtan style is distinguished by its elements of group singing and its use of time-measures. Various Kirtan styles (also called Gharanas) have developed. These are Manoharshahi, Garanhati, Mandarini, Manbhum and Reneti schools, each with its distinctive manner of presentation and incorporating some features of the different classical styles.

Prabhat Samgiit introduces a new gharana of Kirtans called “Prabhat Gharana” kirtans. Musically distinguishing features of Prabhat Gharana are the rules concerning the repeated patterns, the talas involved and the composition-ending pattern. Also, unlike other Gharana kirtans, the bhava (sentiment) of the lyrics contain direct address to God without a third person’s presence.

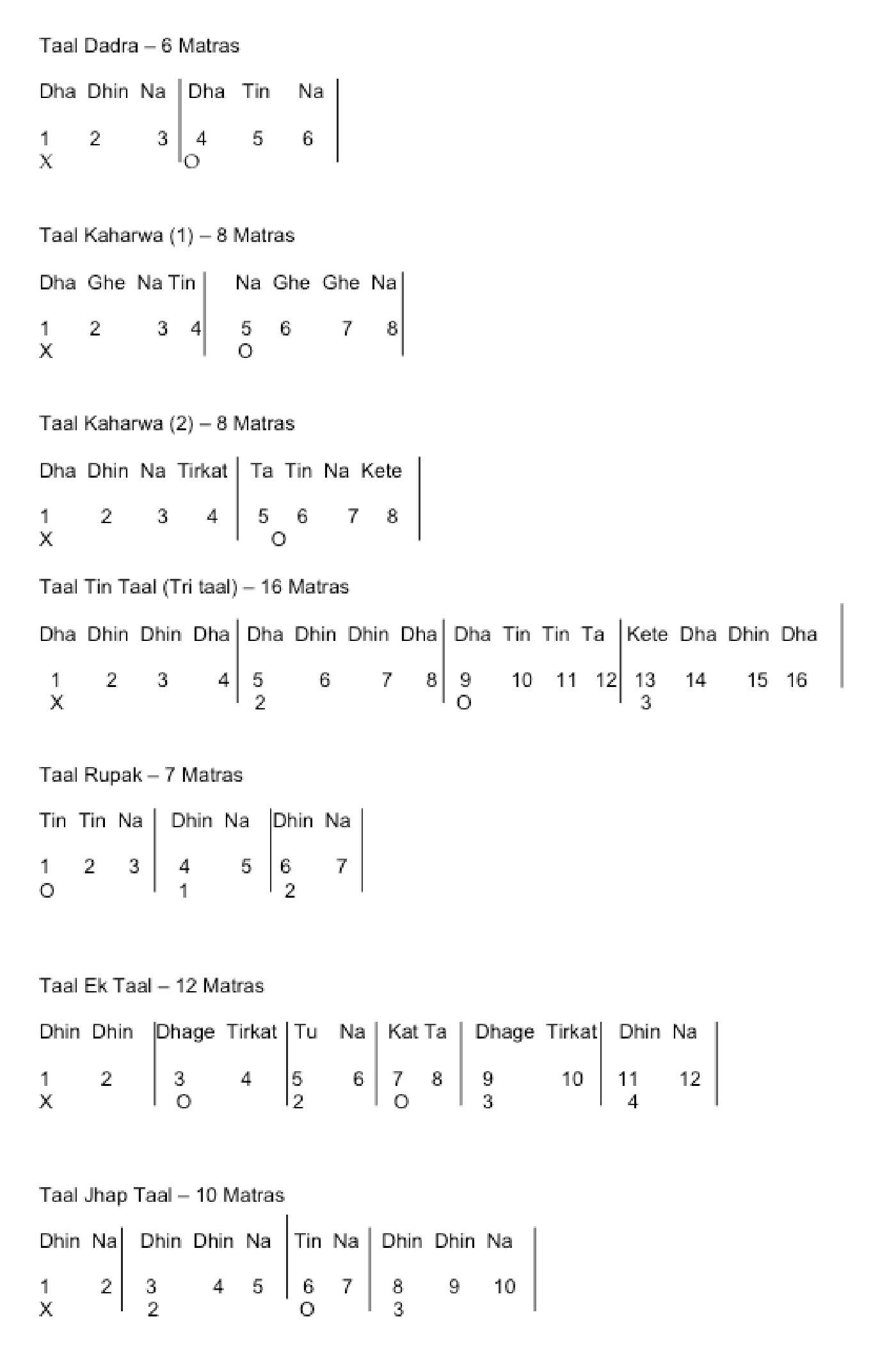

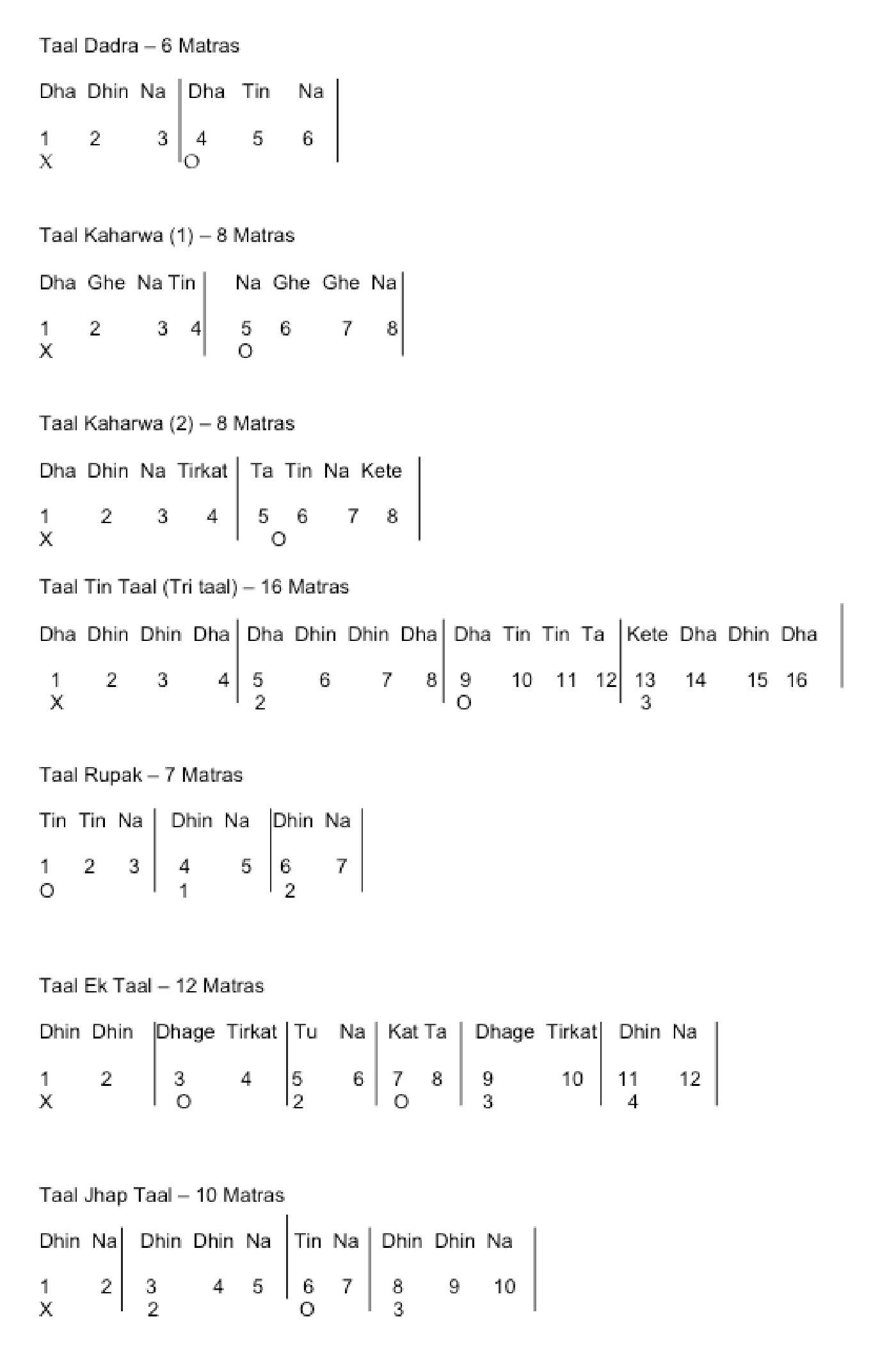

Another important component of music is tala or a cycle of rhythm consisting of a fixed number of beats (called matras). A particular rendering of a raga may be in a particular discipline of a tala, suitable to the musical makeup of that particular composition. The synchronization of raga and tala is an absolute discipline imposed on the artist throughout the rendering of the composition. This synchronization is usually evident at the sum or beat #1 of the cycle of rhythm.

A drone instrument (tanpura) provides the pitch and accompanies performances of classical music. The tanpura provides a subtle, almost hypnotic background effect, of which the audience is often unaware.

Indian classical music uses a wide range of musical instruments, which may be used to accompany vocal or instrumental performances. Commonly heard instruments are the sitar, santoor, sarod, sarangi (string instruments), tabla, pakhavaj (drums), harmonium, shehnai and flute. Percussion instruments are used in solo performances as well.

Raga Descriptions:

1. Raga Darbari Kanada

Darbari Kanada, composed by the great Tansen sometime in 15th or 16th century, is one of the most popular ragas. It is of very serious nature and has a complex descending scale. In ascent, all seven notes are used but in descent the seven notes are used but with a specific movement of notes only. Therefore jaati of the raga is called “Shadav Vakra Sampurna” meaning a “nonlinearly complete” raga. In descent, Sa” to ni is not allowed directly, but must progress by going through dha.

It is of “Kanada Prakar” meaning the note combination ga Ma re Sa is prominent and moving from ga to re must go through Ma. There are as many as 18 ragas that fall into this Prakar, such as Abhogi Kanada, Suha Kanada, Kafi Kanada, Nayaki Kanada etc. and all of them require ga Ma re Sa movement in that way.

In this raga, ga is almost always in the shadow of Ma, and dha is almost always in the shadow of ni. That is, singing of ga requires starting its pitch at Ma and then gradually lowering it to ga in the allocated time of the rhythm. Similarly, dha is treated in the shadow of ni.

This raga is of very serious nature and portrays Viira (bravado) and devotional sentiments. It largely flows in the lower octave and is developed in a slower tempo. Unusual tala such as Jhumara are seen in the renditions of this raga because of its serious and deeper sentiments. The popularity of this raga is so extensive that although it is a strictly classical in nature, the light classical compositions in Bhajans, popular movie songs, and even ghazals also utilize this raga.

Aaroha: Sa, re, ga, Ma, Pa, dha, ni, Sa”

Avaroha: Sa”, dha, ni, Pa, Ma, Ga, Re, Sa

Pakad: Pa ni Ma Pa ni ga, ga Ma re Sa, ni’, Sa, re, dha’, ni’, Pa’, Ma’ Pa’ dha’ ni’ re, Sa.

Vaadi: re

Samvaadi: Pa

Jati: Vakra sampurna

Thaat: Aasawari

Time: midnight.

Jaati: Shadav Vakra Sampurna

Rasa / Sentiment: Bravery, devotion, serious.

Examples in Prabhat Samgiit:

1370

647

2. Raga Bhairavi

Aaroha: Sa, re, ga, Ma, Pa, dha, ni Sa”

Avaroha: Sa”, ni, dha, Pa, Ma, ga, re, Sa

Vadi: Pa or Ma

Samvadi: Sa

Pakad: Sa, re ga Ma, ga re Sa dha’ ni’ Sa

Thaat: Bhairavi

Rasa: Romantic, yearning, devotion

Jati: Sampurna

Time: Morning

Note: Bhairavi allows all 12 notes if used properly. Suited for Bhajan, thumari and light music

Examples in Prabhat Samgiit:

4733

4677

3382 (Nat Bhairavi)

3. Raga Bageshri

Aaroha: Sa, ga, Ma, Dha, ni, Sa”

Avaroha: Sa”, ni, dha, Ma, Pa, Dha, Ma, ga, Re, Sa

Vaadi: Ma

Samvadi: Sa

Pakad: dha’ ni’ Sa Ma Dha ni Dha, Ma ga Re Sa

Thaat: Kafi

Jati: Odav-Sampurna

Time: late night

Note: Pancham used very very scarcely and in avaroha only.

4. Raga Asawari

It has two forms; Asawari (refers to Shuddha Re Asawari) uses shuddha Re, and Komal Rishabh Asawari uses “re”.

Aaroha: Sa, Re, Ma, Pa, dha, Sa”

Avaroha: Sa” ni dha Pa, Ma Pa dha Ma Pa ga, Re Sa

Vaadi: dha

Samvadi: ga

Pakad: Ma Pa dha Ma Pa ga Re Sa

Thaat: Asawari

Rasa: Devotion

Jati: Odav-Sampurna

Time: Morning second prahar

Note: Must go straight from dha to Sa; intermediate effect of ni will feel like raga Jaunpuri.

5. Raga Yaman

Aaroha: Ni’ Re Ga ma Pa Dha Ni Sa”

Avaroha: Sa” Ni Dha Pa ma Ga Re Sa

Vaadi: Ga

Samvadi Ni

Pakad: Ni’ Re Ga, ma Ga, Pa ma Ga, ma, Re, Ni’ Re Sa

Thaat: Kalyan

Rasa: Peace

Jati: Sampurna

Time: Night first prahar

6. Raga Desh

Desh is a popular raga, well suited for light classical and seasonal compositions. This raga is very similar to raga Sorath but unlike in Desh, Ga is not allowed in Sorath. In this raga shuddha Ni (in aaroha) and komal-ni (in avaraoha) are used. Re is the most prominent note (Vaadi) and Pa is next most prominent note (Samvaadi). Vaadi, samvaadi and nyaas notes are generally the resting point of the musical phrases. Proper “conversation” between vaadi and samvaadi allows for the systematic improvisation (samvaad) based on the rules of the raga. Although Desh has similarities with Tilak Kamod and Khamj ragas, the proper use of vaadi helps differentiate them.

Aaroha: Sa, Re, Ma, Pa, Ni, Sa”

Avaroha: Sa”, ni, Dha, Pa, Ma, Ga, Re, Ga, Sa

Pakad: Re Ma Pa Ni Dha Pa, Ma Ga Re, ni’ Sa

Vaadi: Re

Samvaadi: Pa

Thaat: Khamaj

Time: Evening, Night, 2nd prahar.

Jaati: Odav Sampurna

Rasa / Sentiment: light, seasonal, folk tunes, romantic, yearning

Jati: Odav-Sampurna

Examples in Prabhat Samgiit:

4195

4866

668

7. Raga Jogiya / Gunkari

Examples in Prabhat Samgiit:

867

Sounds or notes used in Ragas

1. Sa: Shadaj – Sound of Peacock

2. Re: Rishabh – Sound of bull

3. Ga – Gandhar – Sound of goat

4. Ma – Sound of horse

5. Pa – Sound of Cuckoo

6. Dha – Sound of donkey

7. Ni – Sound of elephant

8. There are 7 shuddha swara – Sa, Re, Ga, Ma, Pa, Dha, Ni. There are 4 komal swaras (re, ga, dha, ni) and one Tivra swara (ma). Thus total of 12 swaras. We represent shuddha swara as capital letter, e.g. “ga” and komal and tivra swara by lower letters e.g. “ga” or “ma”.

9. Notation: Lower octave swara e.g. dhaivat swara as: dha’; and the upper octave dhaivat as: dh”

Introduction to Taals

Matra – Beat (Measure of time)

Tali: Emphasized beat (represented by “X” and #s)

Khali: Not emphasized beat (represented by “O”)